We won our first research grant and we’re excited!

Early this year we were awarded a research grant from the American Educational Research Association (AERA) Grant Program funded by the National Science Foundation. Our proposal was titled: Equity analysis at a large scale: Using small area estimation to get the most from the CRDC school arrest data and Hannah and I will both be serving as Co-Principal Investigators.

This is one of the many reasons it’s been awhile since our last newsletter – there’s interesting work all around us these days – and you’ll hear about more of it in the next few issues. Writing the newsletter is one of my favorite things to do at Civilytics, and I’m aiming for 3-4 more newsletters this year.

In this issue you’ll hear more about our AERA-NSF funded research, learn about the future of public safety being created in Atlanta, Georgia, hear about some recent trainings on how to read a local budget we’ve given, as well as a link roundup.

If someone forwarded this to you – please consider subscribing!

- How we’re researching measuring equity using public data

- What Atlanta can tell us about the future of public safety

- Musical Interlude ~ Sam Fender’s Hypersonic Missiles

- On the road talking about budgets

- Inside baseball – a look at our microbusiness IT

- Link roundup

On to the topics!

How we’re researching measuring equity using public data

We are really excited to have the resources to dedicate to basic methodological research that will benefit the broader field of equity analysis using publicly available data. There are still many ways we can get more useful information from publicly available datasets and we’re excited to get the time and space to demonstrate one.

Below is an excerpt from our winning proposal, edited slightly for clarity and length:

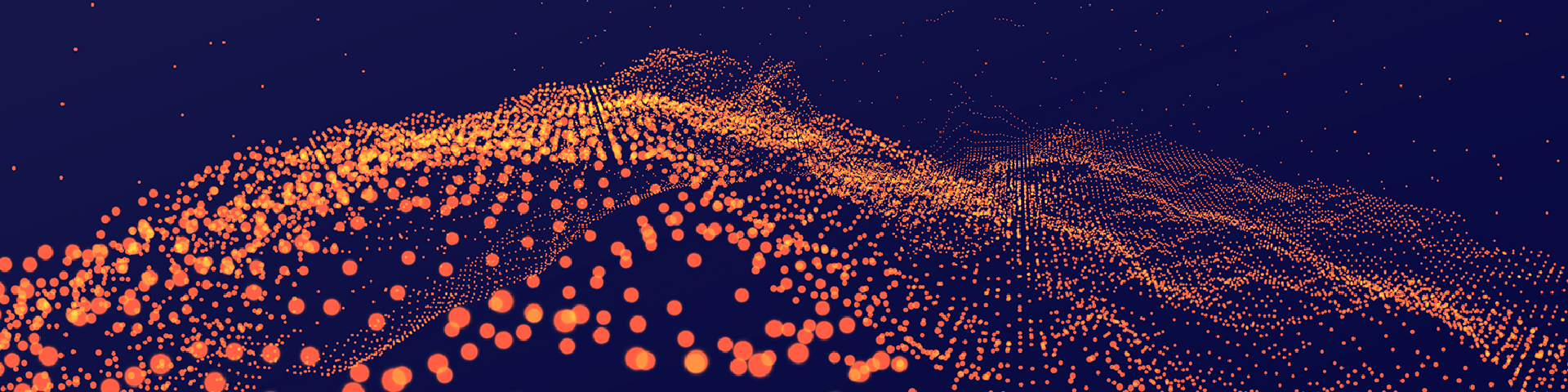

In 2021, we worked with the Tableau Racial Equity Data Hub to create a public dashboard showing student arrest rates and referrals to law enforcement for nearly every public school district in the country. On the dashboard, users can pinpoint their district, view student arrests by race/ethnicity and sex, and compare to other districts of the users’ choice. The dashboard is based on the 2017-18 Civil Rights Data Collection (CRDC). I wrote about it previously here.

Education agency staff and others shared positive feedback about the dashboard, particularly the ability to easily view their own district in the data. But this dashboard and most, if not all, public-facing analyses of arrest rates focus on “raw” or observed counts or rates with some exclusion restrictions based on sample size. This approach provides fodder for critics to dismiss the data as one-year anomalies or as potential data errors. Furthermore, while using rates rather than counts provides a sense of scale and standardization, rates’ sensitivity to slight differences in counts magnifies differences that may not be substantively meaningful (sometimes called the base rate fallacy) and may imply a false precision in reported numbers. Setting exclusion restrictions on sample size can also erase entire student groups from reporting – the opposite of an equity-focused outcome.

Taken together, these issues inhibit equity analyses and efforts to push for change.

Consider a hypothetical district with 400 Black students that arrested 10 of those students last school year. The “raw” arrest rate for Black students would be 25 per 1,000 (such rates are commonly reported on a the per 1,000 scale). But since the data do not actually include 1,000 students, the observed number of arrests is consistent with an arrest rate from 17 to 34 arrests per 1,000—the “true” rate is unobserved.* The arrest rate itself has a probability distribution shaped by both the frequency of the event and the number of trials (i.e., number of students observed).

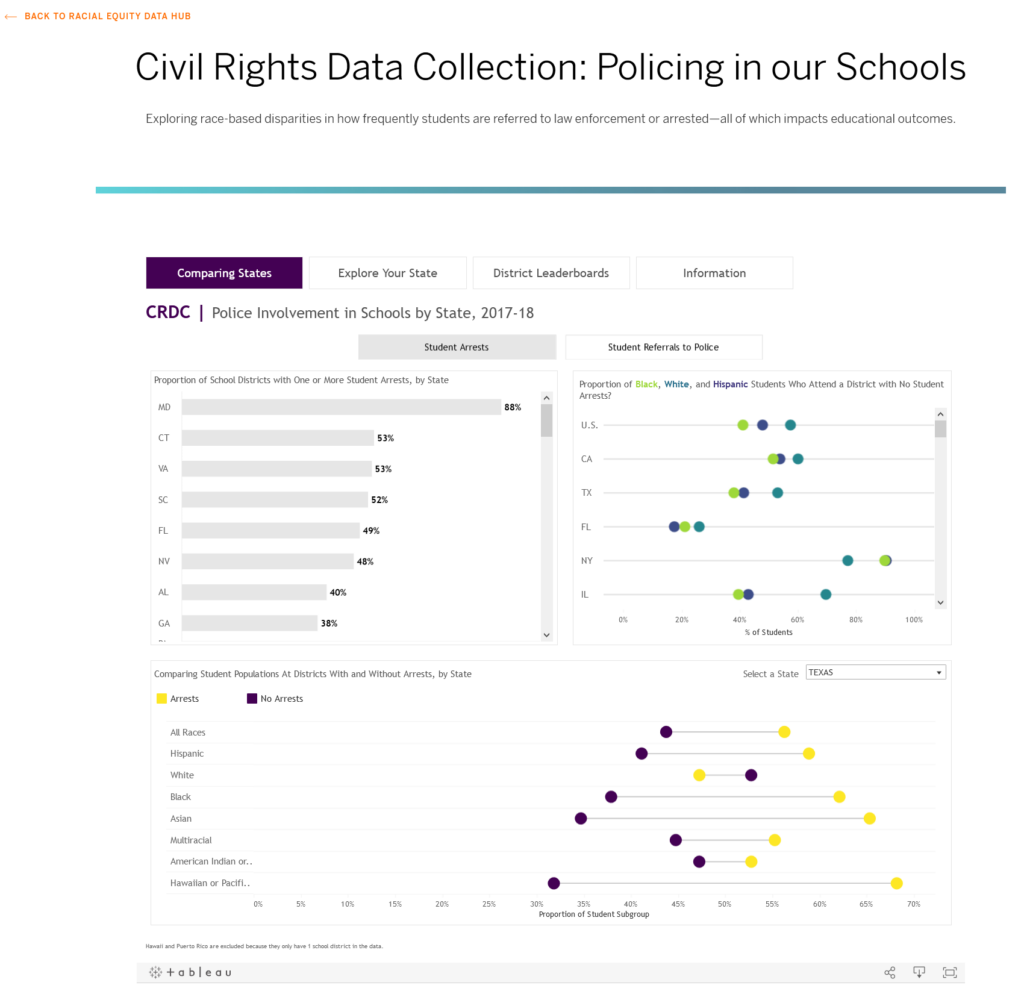

What does this mean for real data and districts? This figure shows the arrest rates for Black and White students in six Maryland districts. Points represent the raw/observed rates calculated from the 2017-18 CRDC, with point sizes proportional to the number of Black and White students in each district. The points show the simplified comparisons that are usually presented.

The curved distributions above the points are simulations based on posterior draws from a Bayesian multilevel binomial regression model – a straightforward way to adjust for the different group sizes. From these distributions, we can see that the data are consistent with definitive Black-White arrest rate disparities in Charles County and Montgomery County Public Schools, but other districts have varying degrees of overlap. From the distributions, it is also clear that Baltimore City Schools arrests Black students at a lower rate than the other Maryland districts shown.

These results come from a basic Bayesian shrinkage model that weights observations toward the grand mean, with the degree of weighting based on population size. This type of analysis is critical to support equity work at the local level, which is currently hindered by insufficient population sizes (the Maryland districts above are larger than most in the U.S.), implausible rates, and data errors.

In our research we will evaluate how different statistical modeling strategies can improve arrest rate precision relative to the costs of model complexity, data requirements and assumptions, and computation time.

Early results are promising and we’ll be sure to keep you updated!

What Atlanta can tell us about the future of public safety

One of our most impressive clients is the Atlanta Policing Alternatives & Diversion Initiative (Atlanta PAD). As a homegrown initiative, PAD works to reduce arrest and incarceration of people experiencing extreme poverty, problematic substance use, or mental health concerns and increase the accessibility of supportive services in Atlanta and Fulton County. PAD provides consent-based direct services to people in need and supports hundreds of community members each month with care navigation and support to connect them to the services they need including food, shelter, employment, and healthcare. Their work is truly groundbreaking!

The policy case for their work is clear – true public safety requires a portfolio of support services for people in need or crisis so they can get well, and not just be detained. The moral case is also clear – many of the people in jail are there as the result of poverty and are disproportionately non-white, low-income, or otherwise marginalized identities. The criminal legal system is made to hold, not help them.

To build a more equitable society means we need systems of care like PAD.

We’ve been helping PAD make a third case – the fiscal case. We wrote a memo illustrating how much money Fulton County has saved through PAD helping people who would have otherwise been booked at Fulton County jail, and how much Fulton County spent by jailing people who PAD could have helped. The key findings looked at PAD’s work from 1/1/2022 through 10/31/2022:

120 people were diverted from jail to PAD by law enforcement this year (through Oct. 31) who would otherwise have been incarcerated at Fulton County Jail. These diversions saved Fulton County an estimated $524,160 that would otherwise have been spent on jail stays.

During this same period, at least 658 people (an average of 65 people every month or two people every day) who were potentially eligible for diversion to PAD were arrested and taken to Fulton County Jail during PAD’s operating hours. Incarcerating these people cost Fulton County an estimated $2,871,144, or around $280,000 per month

PAD’s work is so important and we are grateful to work with them to find new ways to illustrate the impact and success they are having. Follow their amazing work and get a sample of what they’ve been up to here:

At @CityofAtlanta City Hall yesterday presenting PAD's quarterly briefing to @atlcouncil Public Safety & Legal Administration Committee. Check out our presentation ➡️ https://t.co/SGhmc6ERK9 pic.twitter.com/f460Vtuidu

— Policing Alternatives & Diversion Initiative (@PADatlanta) May 23, 2023

Call to action in Atlanta

On the flip side in Atlanta there is an urgent need for funding and your support as constitutionally protected free speech is under assault.

Three bail fund organizers were arrested and charged with financial offenses in a prosecution intended to suppress resistance to the construction of #CopCity, a massive, $90 million + police facility that will serve as a training ground for cops across the country and around the world in how to suppress protest and movements challenging the violence of policing.

As the Atlanta Press Collective reminds us, “Collective bail funds have existed since the dawn of the civil rights movement. When Dr. King was held in Birmingham Jail, churches and community groups including the NAACP came together to fund his $4000 bail – the equivalent of $39,000 today.”

Please keep your eye on what is happening in Atlanta.

And consider supporting those groups leading critical work there:

- Community Movement Builders: https://communitymovementbuilders.org/

- Atlanta Community Press Collective: https://atlpresscollective.com/

- Community Justice Exchange Emergency Rapid Response Fund: https://secure.actblue.com/donate/atlantasolidarity

Musical Interlude

It’s summer! If you want an anthemic catchy jangly guitar song that includes a bit of social commentary, I recommend Hypersonic Missiles by Sam Fender. If you haven’t given Sam Fender a listen and you like Bruce Springsteen, well grab some headphones:

All the silver tongued suits and cartoons that rule my world

Are saying it’s a high time for hypersonic missiles

This is one of my favorite lines of political commentary in a song. It says so much, so quickly.

We’ve been on the road talking about how to read budgets

OSF Opioid settlement budget advocacy training

In May Civilytics was invited to present a training on how to read and monitor state and local budgets for a gathering of advocates working on the public use of opioid settlement dollars. The gathering was hosted by the Open Society Foundations at their New York office. It was something of a professional highlight for me to get to visit!

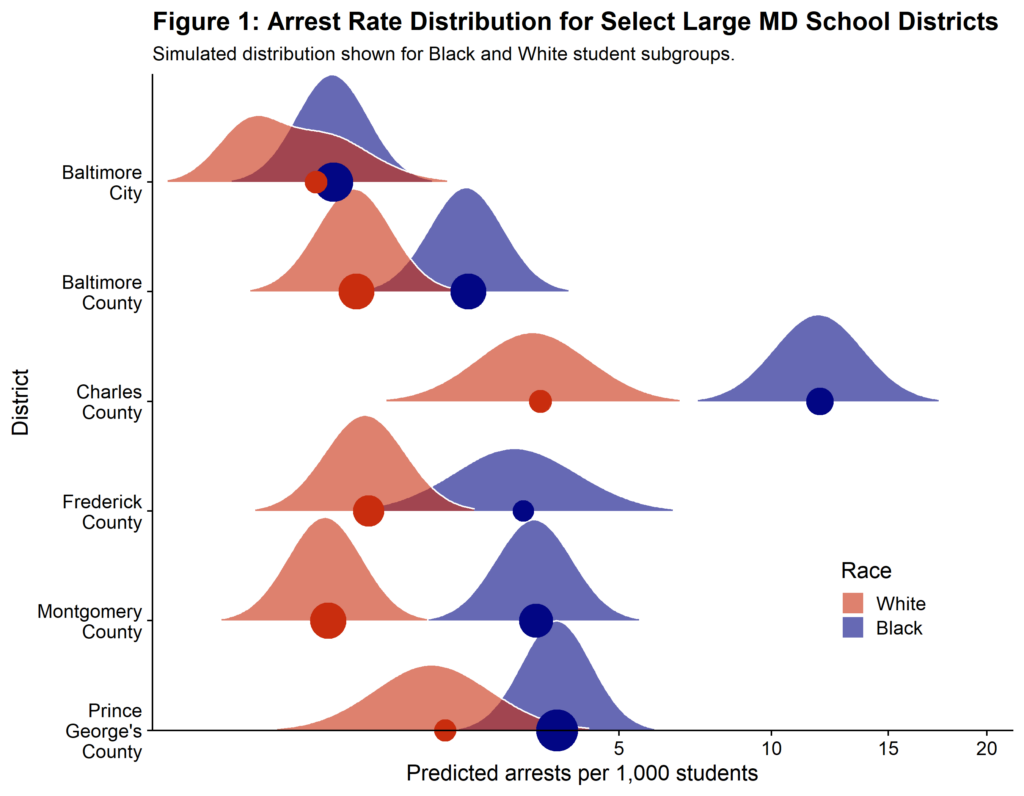

We were brand new to the opioid settlement issue so we were excited to learn more. In a nutshell, opioid settlements refer to a settlement of lawsuits between pharmaceutical opioid distributors and manufacturers and state governments, now totalling over $50 billion. Funds are already flowing and payments will continue for 18 years. The funds are earmarked for specific purposes identified as “opioid remediation” and there is a lot of variation in how states and local governments are interpreting, tracking, reporting, and of course spending these funds.

We saw a lot of parallels to this with the ways the ARPA state and local fiscal stabilization funds intersected with public budgets and how local officials interpreted the regulations around those funds. Combine this with varying extra-budgetary reporting requirements and no rules on how funds are described and reported within budgets, and you have a lot of different ways these funds can be spent and reported.

Yale Liman Colloquium

In April Civilytics was invited to present at the 26th Annual Liman Colloquium hosted by the Arthur Liman Center for Public Interest Law at the Yale Law School. I led a training on “How to read a local and state budget” where I shared some key facts about public budgets, how to find discretionary spending, and walked participants through a hands-on exercise taking a look at the proposed New Haven, CT budget.

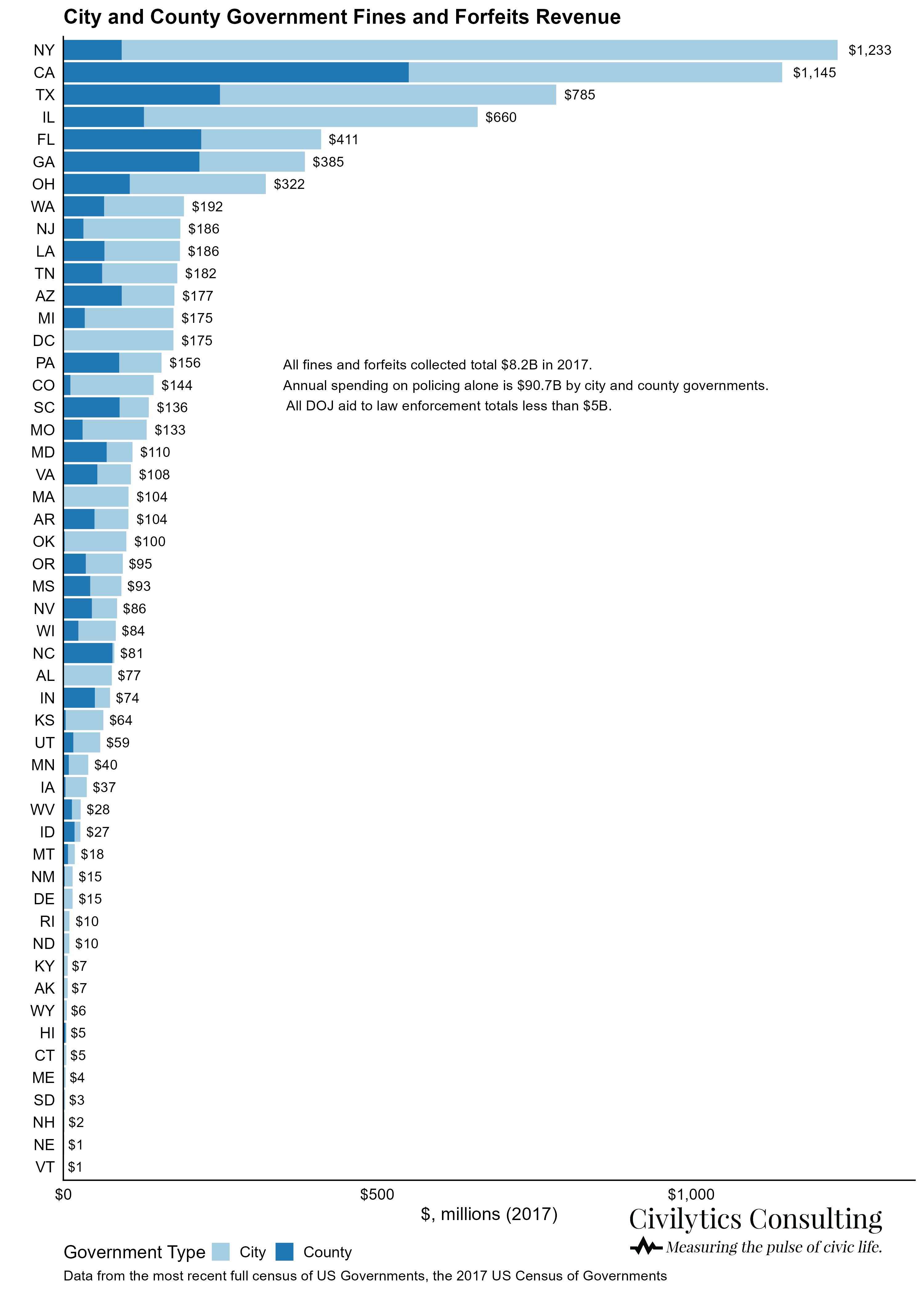

The convening brought together attorneys, advocates, policy experts, and even state supreme court justices around a theme of “Budgeting for Justice: Fiscal Policy and Monetary Sanctions”. In my session I focused on how to put the scope and scale of monetary sanctions imposed by courts into the proper context of city and county budgets. The short answer is that the revenue courts and the criminal legal system generate are a fraction of their operating costs and an even smaller fraction of other sources of revenue available to city and county governments. This revenue is often so small it is not reported independently in budget documents.

It was great to hear about the incredible gains advocates have made in reducing and eliminating fines and fees as a revenue source. I enjoyed learning about legal advocacy work and the ways it intersects with local fiscal policy and social science research and evidence. Thanks to the Liman Center for inviting me!

Inside baseball – a look at our microbusiness IT

I recently took some time to seriously upgrade our data and computing infrastructure here at Civilytics. Running a microbusiness means wearing a lot of hats and one that I enjoy from time to time is finding, deploying, and connecting databases, applications, and compute resources to help us get our work done.

I covered our basic infrastructure in a past newsletter. Check it out.

It’s still largely the same today with a few tweaks, upgrades, and a lot more resiliency. If you’re interested in that side of things – give it a read!

Link roundup

A great presentation of small area estimation to illustrate COVID infection rates and uncertainty

A great example of how to communicate a statistical model for decision-making. The statistical model incorporates a range of information to make estimates of the infection rate of COVID-19 in US counties. The important information is summarized with uncertainty shown on the homepage, and then users can zero in on specifics about individual county estimates including seeing the input data and comparing previous predictions to observed data. There’s a lot of great lessons here about how to communicate complex data analysis well.

When forensic science is anything but science…

Radley Balko’s newsletter is always informative, but this issue deserves a special callout. Ballistics analysis, matching the pattern of a bullet to the gun that fired it, is a staple of crime and thriller storytelling and has a long history. Unfortunately, as Balko describes in a tour of the history of ballistic analysis, the “science” of forensic science is aspirational. Ballistic analysis is based on pattern matching and relies on untested assumptions about the uniqueness of ballistic markings and the consistency of pattern detection by ballistics analysts. Recently a judge denied the use of expert testimony from a forensic firearm analyst in a case in Illinois – the first time such evidence has been barred outright. Over 100 years of legal precedence is being called into question.

As always, thank you for reading!

Jared

- *These are the 5th and 95th percentile events simulated from 10,000 draws of a binomial distribution with probability of 0.025 and 1,000 trials.